AI coding agents have fundamentally shifted from simple autocomplete tools to sophisticated systems that can understand entire codebases, coordinate multiple specialized workers, and integrate with external services through standardized protocols. This report provides the deep technical knowledge developers need to effectively use, configure, and build AI coding agents.

Configuration files are the foundation of effective AI agents

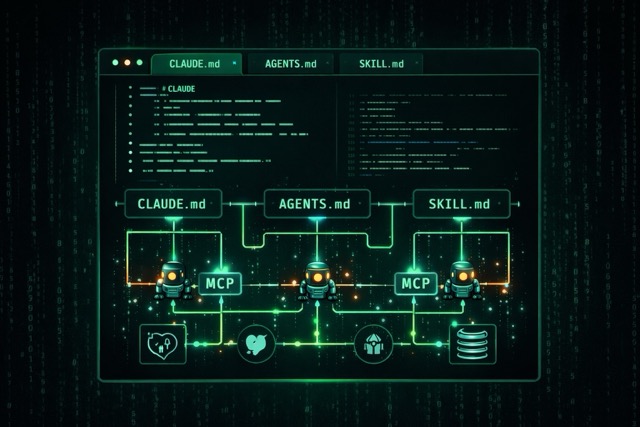

The emergence of AGENTS.md and CLAUDE.md files represents a crucial standardization in how developers communicate with AI coding assistants. Think of these files as README files for machines—they provide persistent, project-specific context that transforms general-purpose AI into specialized collaborators.

AGENTS.md emerged from collaborative efforts across OpenAI, Google, Cursor, and others, and is now stewarded by the Agentic AI Foundation under the Linux Foundation. As of January 2026, over 60,000 open-source projects on GitHub use this format. Before this standardization, developers maintained separate files for each tool: .cursorrules, .windsurfrules, .clauderules, and .github/copilot-instructions.md—a fragmented approach that AGENTS.md consolidates into one universal file.

CLAUDE.md is Anthropic’s specific convention for Claude Code, functioning identically in purpose but optimized for Claude’s capabilities. The file loads automatically into Claude’s context window at session start, becoming part of its system prompt and acting as project memory that persists across sessions.

The key distinction between these configuration files and traditional documentation is their audience: README.md uses informal phrases like “set up your environment” while AGENTS.md requires precise, step-by-step instructions with exact commands and flags.

The most effective AGENTS.md files share five characteristics:

- Commands appear early with full flags and options

- Code examples replace prose explanations

- Clear boundaries define what agents should never touch

- Specific tech stacks are named with versions

- Six core areas are consistently covered: commands, testing, project structure, code style, git workflow, and boundaries

# AGENTS.md

## Project Overview

Next.js 14 e-commerce app with App Router, Stripe, and Prisma ORM.

## Commands

- `npm run dev`: Start development (port 3000)

- `npm run test`: Jest tests

- `npm run lint`: ESLint check

## Boundaries

- Always do: Write to `src/` and `tests/`, run tests before commits

- Ask first: Database schema changes, adding dependencies

- Never do: Commit secrets, edit `node_modules/`Both files support hierarchical organization in monorepos. The OpenAI Codex repository contains 88 AGENTS.md files distributed across its codebase, with agents automatically reading the nearest file to the work being done. For CLAUDE.md specifically, files in ~/.claude/CLAUDE.md provide global defaults, project root files set team-wide conventions, and subdirectory files load on-demand when Claude works in specific areas.

Keep these files concise: under 150 lines for AGENTS.md and under 300 lines for CLAUDE.md, as research indicates frontier LLMs reliably follow approximately 150-200 instructions.

Subagents enable sophisticated task decomposition and context management

Modern AI coding tools have evolved beyond single-agent systems into multi-agent architectures where specialized workers coordinate through orchestration patterns. Understanding these patterns is essential for developers using tools like Claude Code, Cursor, or Devin—and crucial for those building custom agent systems.

Claude Code’s subagent system is the most thoroughly documented implementation. It includes three built-in subagents:

- Explore Subagent using Haiku for fast, read-only codebase exploration

- Plan Subagent using Sonnet for gathering context before presenting plans

- General-Purpose Subagent using Sonnet for complex multi-step tasks requiring both exploration and modification

Each subagent operates in its own isolated context window, preventing pollution of the main conversation thread. Critically, subagents cannot spawn other subagents—this architectural decision prevents infinite nesting and maintains predictable resource usage.

The primary benefit of subagents is context management. A main thread handling exploration directly might accumulate 169K tokens of noise, while delegating to a subagent that returns a distilled 2K summary keeps the main thread at just 21K tokens—8x cleaner. The subagent burns 150K tokens off-thread, then returns only the signal.

Cursor 2.0 introduced a multi-agent interface supporting up to 8 parallel agents in isolated workspaces using Git worktrees or remote machines. Its proprietary Composer Model uses a Mixture-of-Experts architecture with reinforcement learning training, claiming 4x speed improvements.

Devin 2.0 emphasizes parallelization with isolated VMs and a dual-agent system separating high-level planning from implementation execution. Its Knowledge Base feature enables team-wide behavioral consistency across sessions.

When deciding whether to spawn subagents or handle tasks in the main agent, apply this framework:

Use subagents when:

- Context preservation matters

- Parallel work is beneficial

- Specialized expertise is needed

- Complex multi-step tasks would pollute the main conversation

Keep tasks in the main agent when:

- They’re single and well-defined

- They require interactive back-and-forth with the user

- Write operations to the same files are involved (multiple agents editing the same files creates merge conflicts)

# Claude Code subagent configuration (.claude/agents/code-reviewer.md)

---

name: code-reviewer

description: Reviews code for quality and best practices

tools: Read, Glob, Grep # Read-only tools only

model: sonnet

permissionMode: plan # Cannot make changes directly

---

You are a senior code reviewer focused on code quality,

security vulnerabilities, and adherence to project conventions.The orchestration patterns used across these tools fall into recognizable categories:

- Sequential pipelines where Agent A feeds Agent B feeds Agent C work well for progressive refinement

- Parallel execution where multiple agents work simultaneously suits independent tasks

- Hierarchical structures where manager agents oversee workers scale to large problems

- Generator-critic patterns where one agent creates and another validates enable quality control loops

Skills extend agent capabilities through modular expertise packages

Skills represent a newer abstraction in the AI agent ecosystem—they’re modular, filesystem-based resources that provide domain-specific expertise through packaged instructions, metadata, and optional resources like scripts and templates. Unlike tools which execute discrete actions, skills encode how an agent should approach problems in a particular domain.

The Agent Skills Standard (agentskills.io) has emerged as an open specification adopted by Microsoft, OpenAI, Atlassian, Figma, Cursor, and GitHub. The standard uses a progressive disclosure architecture with three levels:

- Level 1 loads only name and description metadata (~100 tokens) at startup

- Level 2 loads the full SKILL.md instructions (<5,000 tokens) when the skill is activated

- Level 3 resources like scripts and reference documents load on-demand

This architecture solves a critical token economics problem. One GitHub MCP server can expose 90+ tools consuming 50,000+ tokens of JSON schemas before any reasoning begins. Skills encode equivalent domain expertise with dramatically lower schema overhead.

# SKILL.md for backend API development

---

name: backend-api-development

description: Assist with RESTful API development and testing.

Use when building APIs, writing endpoint code, or creating API tests.

version: 1.0.0

tags: [backend, api, rest, testing]

---

## Instructions

When creating FastAPI endpoints, follow these patterns:

from fastapi import FastAPI, HTTPException, Depends

from pydantic import BaseModel

class ItemCreate(BaseModel):

name: str

price: float

@app.post("/items/", response_model=Item)

async def create_item(item: ItemCreate):

return {"id": 1, **item.dict()}

Always validate input parameters, use proper HTTP status codes,

and document all endpoints with OpenAPI annotations.Claude’s computer use represents skills at the infrastructure level—enabling Claude to interact with computers through pixel-accurate mouse movements, keyboard input, and screen reading. The system achieved 14.9% on OSWorld benchmarks using screenshot-only input, nearly double the next-best AI system’s 7.8%.

When building custom skills: create focused, single-purpose skill files; use clear metadata descriptions so agents know when to activate them; include concrete code examples rather than abstract explanations; and treat skills with the same security caution as installing software.

MCP standardizes how AI connects to external tools and data

The Model Context Protocol (MCP) is Anthropic’s open standard that functions as a “USB-C port for AI applications”—providing a standardized interface for AI systems to connect with external data sources, tools, and services. Released in November 2024, MCP has been adopted by OpenAI (March 2025), Google DeepMind, and Microsoft, transforming what was previously an N×M integration problem into a simpler N+M setup where each party implements the protocol once.

MCP follows a client-host-server architecture built on JSON-RPC 2.0. The Host (Claude Desktop, IDEs, AI applications) coordinates multiple MCP Clients, each maintaining a 1:1 connection with an MCP Server. Servers are lightweight programs that expose specific capabilities—the GitHub server provides repository operations, the Slack server enables messaging, the PostgreSQL server allows database queries.

The protocol defines three core primitives:

- Resources are application-controlled, read-only data like files and API responses

- Tools are model-controlled executable functions that the LLM can invoke with user approval

- Prompts are user-controlled templates for specific tasks

# Building a custom MCP server with FastMCP

from mcp.server.fastmcp import FastMCP

import httpx

mcp = FastMCP("weather")

@mcp.tool()

async def get_forecast(latitude: float, longitude: float) -> str:

"""Get weather forecast for a location.

Args:

latitude: Latitude of the location

longitude: Longitude of the location

"""

async with httpx.AsyncClient() as client:

response = await client.get(

f"https://api.weather.gov/points/{latitude},{longitude}",

headers={"User-Agent": "weather-app/1.0"}

)

data = response.json()

forecast_url = data["properties"]["forecast"]

forecast = await client.get(forecast_url)

return format_forecast(forecast.json())

if __name__ == "__main__":

mcp.run(transport="stdio")The available MCP server ecosystem is substantial. Official reference servers include Filesystem (secure file operations), Git (repository manipulation), Memory (knowledge graph persistence), and Fetch (web content retrieval). Popular community servers cover GitHub, GitLab, Slack, PostgreSQL, MongoDB, Notion, Jira, Playwright (browser automation), and Brave Search.

SDKs are available in Python, TypeScript, Kotlin (maintained with JetBrains), C#, Java, Rust, and Go. When building servers, critical implementation details matter: STDIO servers must never write to stdout (it breaks JSON-RPC), using stderr for all logging; HTTP servers can use standard output normally.

Configuration for Claude Desktop connects multiple servers simultaneously:

{

"mcpServers": {

"github": {

"command": "npx",

"args": ["-y", "@modelcontextprotocol/server-github"],

"env": {"GITHUB_PERSONAL_ACCESS_TOKEN": "ghp_xxx"}

},

"postgres": {

"command": "npx",

"args": ["-y", "@anthropic/mcp-server-postgres",

"postgresql://user:pass@localhost/db"]

}

}

}Security requires careful attention. MCP uses OAuth 2.1 with PKCE for authentication, short-lived scoped tokens, and dynamic client registration. Key risks include server impersonation, consent fatigue leading to over-permissioning, credential exposure in plaintext config files, and prompt injection through malicious tool responses.

Where do prompts fit in all this?

With all this talk of configuration files, subagents, skills, and protocols, it’s worth stepping back: prompts are still the foundation. Everything else builds on top of them.

Here’s how the layers stack up:

- Prompts are the atomic unit. Every interaction with an AI agent starts with a prompt—your natural language request that tells the agent what you want.

- CLAUDE.md / AGENTS.md are persistent prompts. Instead of repeating project context every session, these files inject it automatically. They’re prompts that live in your repo.

- Skills are specialized prompt packages. They bundle domain expertise into reusable modules that activate when relevant.

- MCP connects prompts to the outside world. It lets your prompts trigger actions in external systems—databases, APIs, browsers.

- Subagents are prompt delegation. The main agent prompts specialized workers to handle subtasks, keeping context clean.

The good news: you don’t need to understand all these layers to get value from AI coding agents. Modern tools like Claude Code and Cursor are already remarkably capable with just conversational prompts.

Getting started is simpler than you think

Don’t let this technical depth intimidate you. The best way to learn is to start using these tools today:

Step 1: Just start prompting. Install Claude Code or Cursor and start asking it to help with real tasks. “Help me refactor this function.” “Find where this API is called.” “Write tests for this module.” The agents are already powerful enough to be useful without any configuration.

Step 2: Create a CLAUDE.md or AGENTS.md when you notice repetition. After a few sessions, you’ll find yourself explaining the same things: “This is a Next.js project,” “We use Prisma for the database,” “Run tests with npm test.” That’s your cue to create a configuration file. Start with 20-30 lines capturing the essentials.

Step 3: Expand as needed. Add boundaries when the agent touches things it shouldn’t. Add code style notes when it formats things differently than you prefer. The file grows organically based on real friction points.

The configuration files, skills, MCP servers, and subagent patterns all exist to solve problems you’ll encounter naturally as you use these tools more. You don’t need to master them upfront—let your actual workflow guide what you learn next.

Conclusion

The AI coding agent ecosystem has matured into a coherent technical landscape with clear standards and patterns. But you don’t need to understand all of it to get started.

Start with prompts. Use Claude Code, Cursor, or Copilot on your actual projects. Let natural language do the heavy lifting.

Graduate to configuration files. When you find yourself repeating context, capture it in a CLAUDE.md or AGENTS.md file. Start small and grow it based on real needs.

Explore the deeper layers when you hit limits. MCP servers, custom skills, and subagent patterns exist to solve specific problems. You’ll know when you need them.

The gap between having used an AI coding agent and never having tried one is enormous. The gap between basic usage and advanced configuration? That closes naturally with practice.

Open your terminal, start a conversation, and let the agent help you build something.